Steel Shot and Chokes

- Rus Hinkle

- Aug 6, 2024

- 10 min read

Updated: Dec 3, 2024

Lead-free shot has been mandated for waterfowl hunting in the United States for over 30 years now, yet there is still a larger percentage of the waterfowl hunting population that does not know you cannot shoot steel through all guns and chokes. Today, we are hopefully going to change that. Unless you want to wind up looking like Wile E. Coyote, Super Genius (or worse), I suggest you pay close attention to the rest of the article. Class is in session.

Photo credit: Warner Bros.

Toxic shot was banned for waterfowl hunting in the United States in 1991. Prior to this, nearly all shotgun shells’ shot core were lead. Today, the story is very different. Let’s first start with the difference in the two materials.

Lead (Pb 82) is a natural heavy metal chemical element that is found on nearly every continent. Lead isotopes are formed from natural nuclear decay from other elements, such as Uranium and Thorium. Lead exhibits an unusual very dense, but malleable metallic form at room temperature, and has a relatively low melting point. Lead was first primarily used in ancient Egypt, Greece, and China for cosmetics, currency, enamels, and weights. Rome was infamous for using lead pipes for plumbing and as a spice. As a heavy metal, lead is incredibly dangerous to the body if ingested and can cause severe neurological damage. During the middle ages, lead became the primary use for projectiles in cannons and firearms and has been used ever since. This was due to the fact that lead bullets were relatively cheap to manufacture and did not cause as much damage to the bore as iron shot did. Due to its high density, lead core projectiles also retain velocity better than iron or steel core on a one-to-one comparison. Lead became the standard firearms projectile simply due to its high weight, high density, ease of manufacture, and low cost. With the introduction of smokeless powder, rifled projectiles began rattling themselves apart in the barrel due to the increased friction from the higher-pressure charge. Swiss Colonel Eduard Rubin would later invent the copper metal jacket for projectiles in 1882.

Steel is an alloy primarily composed of the elements iron (Fe 26) and carbon (C 6). Steel has a relatively high tensile strength and fracture resistance compared to lead, and is also much less dense. Steel is formed by the atomic crystallization of iron and a hardening agent (carbon) in a high-temperature environment, such as a blast furnace. As iron makes up nearly 5% of the Earth’s crust, it is one of the world’s most common elements. It is unknown when steel was first discovered, but recent excavations date its earliest known use to circa 1800BC in what is now Turkey. Steel was produced in he British islands as early as 400BC, and Hannibal’s Carthage adopted steel into its military during the Second Punic War against Rome. Hannibal’s use of steel forced the Romans to drastically change tactics, and he was on the verge of conquering Rome, but he was ultimately defeated by Scipio Africanus in a counter-invasion of Carthage. Steel eventually incorporated its way into firearms technology, being the base metal for most gun barrels and actions since the early days of matchlocks. Steel core ammunition, without a sufficient jacket made of a more malleable material, such as lead or copper, can cause significant damage and premature wear to a firearm’s bore primarily due to friction alone. If the steel of the projectile is harder than the steel of the barrel, the projectile will cause significant premature wear of the bore, and can sometimes even re-shape the bore completely. Steel is also currently used in special application ammunition, particularly light ball ammunition.

Now that we have the history out of the way, let’s focus on how it pertains to today’s lesson; shotguns. As previously mentioned, the United States has a nationwide ban on using “toxic” ammunition for waterfowl hunting since 1991. “Toxic” ammunition includes lead, which most ammunition’s core is made of. With shotguns specifically, using an ammunition whose core is not as malleable as lead can lead to significant problems.

Metallurgy

As shotguns are relatively low-pressure firearms compared to rifles and pistols, the barrels are usually not as hard or thick as a rifle or pistol barrel. For example, a typical 12g 3” magnum should not exceed 11,500PSI and a 3.5” supermagnum shotshell should not exceed 14,000PSI according to SAAMI specifications. Meanwhile, the maximum pressure for a 22LR is a whopping 24,000PSI in comparison- almost double a supermagnum but at 1/100th the recoil! Ergo, if the shot material is harder than the barrel material, the shot will cause significant damage to the bore each time the gun is fired. This phenomenon also applies to rifle and pistol ammunition that lack a soft (usually copper) jacket surrounding the hardened steel core. Luckily in recent years, bismuth ammunition has become widely available (although not cheap), but we will talk more about bismuth later. Most modern shotgun barrels are made to be able to withstand steel shot unless otherwise noted. However, many shotguns manufactured in the United States prior to the 1991 ban have even softer barrels. As a general rule, you should never fire steel ammunition through a pre-1991 shotgun as a safety precaution (I would personally also apply this to copper core ammunition as well, but we will talk about this later).

Chokes

Unique to the shotgun world is the muzzle choke. The choke changes the pattern of the shot via constriction of the bore to either widen or condense the shot pattern. Normally, his is not a problem for malleable material such as lead or bismuth. It does become an issue, however, when shooting a very hard material such as steel or copper core ammunition. As the shot goes through the choke, it is constricted through the conical construction of the choke itself. As lead is very malleable, lead shot can easily handle being shot through even some of the tightest chokes. Steel, meanwhile, has limitations. As steel is not as malleable as lead, when being forced through too tight of a choke, the shot effectively cannot “get out of the way” of itself, and one of two things will happen:

1. The choke is weaker than the shot, and the choke itself will give way and blow out, force-welding itself to the barrel

2. The choke is stronger than the shot, and constricts the shot so much that the shot slows down enough to cause an over-pressure buildup behind the shot cup/wad, causing the barrel wall to either bulge or rupture

So, how do we prevent this from happening when we are required to use steel shot for waterfowl?

The answer is simple:

1. USE A CHOKE THAT IS MADE FOR STEEL SHOT.

2. Do not use steel shot, but another “non-toxic” material

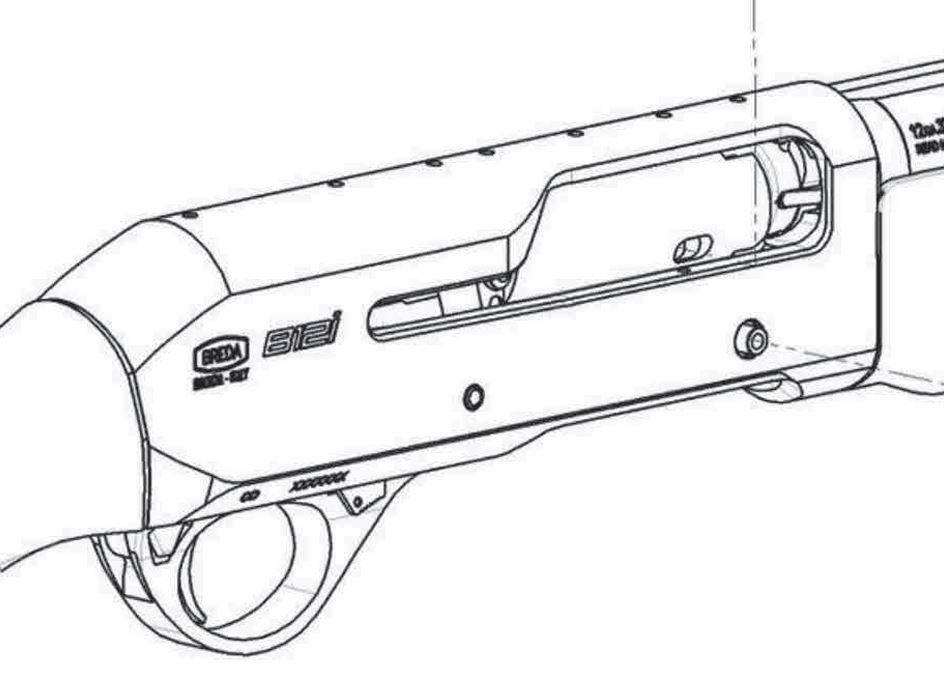

It is quite astounding to me that people refuse to simply read any warnings on the chokes themselves or in the user manuals. For example, Breda chokes indicate both in the user manual and on the chokes themselves if they are safe to shoot steel shot. The factory Cylinder, Improved Cylinder, and Modified are perfectly fine to shoot steel shot through. However, the Improved Modified, and the Full are not safe to shoot steel through. If you want to shoot steel through a choke constriction tighter than a Modified, you will have to purchase an aftermarket choke that is rated for such. Why is this? To put it simply, it is a combination of two factors: the choke design, and choke materials. As of writing this article, I am only aware of two factory choke designs than are rated for steel shot from the Cylinder out to Full: Fabarm Exis/Inner, and Browning Invector type. Breda uses a Crio Plus type. Let’s take a short detour talk about choke design.

Choke Design

Of the myriad of different choke designs out there, most of the industry has standardized on a few designs; Mobil, Crio, Optima, Invector, Remchoke, and Tru choke to name a few. Some companies will insist on using their own design, such as the previously mentioned Fabarm, or even Zoli and Bernardelli. In this article I am only going to cover 3 types: Invector, Crio Plus, and Exis as most choke designs will be similar to these three. External bore chokes that thread on to the outside of the barrel also exist, but we will not cover those here.

All in-bore choke designs share three common attributes; they require a choke recess, they have screw threads, and they constrict the muzzle diameter through a conical shape. As Breda uses a Crio Plus type, we will start with this as the standard to compare the Invector and Exis to.

Photo Credit: Benelli USA

As you can see in the above photograph, the Crio Plus choke has its threads near the center of the choke with a solid collar above the threads. This style of choke is the best “compromise” between various factors and typically leads to more consistent patterns when compared to other chokes on a 1:1 basis. The collar above the threads is present to increase the wall thickness of the choke at its most constricted point; the muzzle. The collar is also present as to not have the threads end right to the muzzle, which have a tendency to roll over (as in the case with Mobil and Maxis chokes) and can in rare cases prevent chokes from fully seating or being screwed in smoothly. The threads in the middle of the choke allows for two points of contact on the barrel: one at the rear of the choke where the choke bottoms-out on the shelf of the choke recess in the barrel, and the screw threads themselves. The distance between these two points allows the choke to have two points of contact, one at nearly each end of the choke. This prevents the choke from “walking” inside the bore, and allows for more consistent patterning as the choke does not have a tendency to move from shot to shot. The downside to this design is that it cannot accept steel ammunition through chokes tighter than the Modified, as the thread location compromises wall thickness. This is also typical of nearly all other factory choke designs; the Modified is the tightest you can usually shoot steel through.

Photo credit: Browning Arms Co.

The Browning Invector and Invector Plus by comparison can shoot steel through all standard constrictions according to Browning. This is because these choke types have their threads at the bottom, and thus only utilize a single point of contact in the barrel, allowing for thicker choke walls at the tightest point of constriction. As a result, while you can shoot steel through all the standard chokes. However, they will not pattern as consistently as a Crio Plus will, or even a Mobil for that matter. The Invector DS, however, retains the two point contact that the Crio Plus has. Due to the overall length of the choke, the conical shape has a much more gradual taper versus the Invector and Invector Plus chokes. The Invector DS design still occasionally suffers from aforementioned rolled threads due to them being directly at the muzzle.

Photo credit: Fabarm USA

The Fabarm Exis/Inner choke style combines the two-point and collar system of the Crio Plus, but additionally elongates the choke. The patented interior conical shape is also a gradual slope rather than a straight conical shape.

Photo credit: Fabarm S.P.A.

As such, the Fabarm Exis/Inner type combines the best of both worlds, allowing the user to shoot steel through all but the Extra Full constriction while keeping a consistent pattern from shot to shot. The only downside to this type comes down to price. Fabarm will not license this design to other firearms manufacturers, so it remains proprietary to Fabarm alone until the patent expires. As of writing, Fabarm’s least expensive firearm has an MSRP of $1,425, and the chokes cost $71 each on the FabarmUSA webstore. For comparison, most aftermarket steel-compatible Crio Plus chokes range from $60-$120 each, and standard Invector and Crio Plus chokes can be had factory new for as little as $25 and $35 respectively. For the time being, the Fabarm choke, while probably the best design out there, is not exactly financially viable for a large percentage of the shotgun market.

Photo credit: Kicks Ind.

Aftermarket choke designs do not have to conform to certain metallurgical standards set out by the factory engineers, only the external dimensions. As such, there is a wide-variety of aftermarket options for nearly all public choke designs. Some are extended, some are flush with the muzzle. Some aftermarket chokes are made of hardened steel and can handle steel shot through even the tightest constrictions. Other designs utilize ported muzzle extensions to serve as a “relief valve” of sorts to prevent over-pressure from slowing down the shot during constriction. Always consult the choke manufacturer before shooting steel through an aftermarket choke.

Options

Now that we have established why chokes work the way they do, we can circle back to the options you have for shooting steel through certain chokes. Typically speaking, steel should not be shot through anything tighter than a Modified choke unless otherwise specified. This especially applies to fixed choke barrels, as significant and even fatal damage can occur. So what are your options for shooting steel through your shotgun? Use a choke rated for steel shot. “But what if my tighter chokes aren’t rated for steel?” you may ask. There are two options:

1. Use an aftermarket choke that is rated for steel shot in the constriction you want

(Note that there may be warranty issues for this option)

2. Use Bismuth, Copper, or other “non-toxic” ammunition

Non-Toxic Ammunition

Within recent years, bismuth, copper, and tungsten ammunition have become prevalent in the industry. Bismuth shot is as malleable and has nearly the same density as lead. So much so that ballistically speaking, they are almost identical. Bismuth is also considered “non-toxic”, and does not have the same heath risks associated with lead. Bismuth, however, is not as abundant as lead and thus is more expensive. Bismuth shot retains the same restrictions as lead shot. Copper-core ammunition is also becoming quite prevalent, but is nowhere near as inexpensive as steel or lead shot. Considerations should also be taken as copper is also not as malleable as lead, but is more malleable than softer steel. A good rule of thumb is to treat copper-core shot like steel shot when considering choke options. Tungsten has been recently making waves through the turkey hunting crowd, and has slowly migrated into the waterfowl industry. Tungsten (typically called TSS/Tungsten Super Shot) is nearly twice as dense and heavy as lead, and is notable for having the highest melting point of all elements at over 6,000 degrees. Tungsten should also be treated like steel shot, and cannot be shot through most older firearms. Tungsten is also a rare metal, with China, Russia, and Vietnam being the largest producers of the element. As such, tungsten is incredibly expensive to shoot sometimes costing upwards of $10 per shell alone.

So, now that you are better informed on steel shot and what chokes you can use, hopefully you will not end up like Wile E. Coyote, Super Genius, and blow your barrel up or get your choke stuck due to ignorance regarding shot material and chokes. It is on average twice per month that I have to remove a customer’s stuck choke because they shot steel through their Full or IM choke. The customer will then usually become irate when I inform them that I will have to charge for the service of removing the stuck choke, as it is not covered by warranty.

All joking aside, shooting improper ammunition through the wrong choke can be fatal. I cannot stress how dangerous it is to shoot steel through a choke it is not rated for. At minimum, is it worth risking $100 for, and at worst is it worth risking your life? Use your brain; read your chokes, read your user manual.

P.S. Your chokes need love too, don’t forget to clean them!

Rus Hinkle

Banshee Brands Lead Gunsmith

Effective code snippets function like memorable lines from a textbook that can be referenced at any time. Through UNICCM, learners discover the best ways to store these pieces of logic in integrated development environments. They serve as a reliable foundation for any source code.

In national datasets, the average uk salary reflects broader workforce dynamics, including promotion timelines and seniority. Earnings often mirror responsibility levels. UNICCM highlights structure within pay progression.

At UNICCM, Year 5 Religious Education encourages students to examine the connections between different religious traditions. By exploring key teachings and practices, students gain a deeper respect for religious diversity and a better understanding of how faith influences personal and societal values.

Understanding practice and practise is key to mastering British English spelling. The difference lies in their grammatical roles — one is a noun, the other a verb. Practice is the noun, and practise is the verb. Knowing this helps improve your writing accuracy and professionalism. Learn more English spelling tips at UNICCM.

Prepared to advance your career? At the College of Contract Management, our adaptable online courses in Contract Management, Data Science, CAD Design, and Health & Social Care are tailored to fit your lifestyle and enhance your success. Connect with thousands of experts who have changed their destinies—begin now and turn it into reality!